Examining historical documents to understand how they fit into a grander context: the discipline of Japanese History

Hirofumi Yamamoto

Professor

Historiographical Institute / Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies (concurrent post)

Professor Yamamoto studies the political history of Japan, focusing on the era from the administration of Hideyoshi Toyotomi to the early Edo period. He has pored over vast amounts of information from historical archives in order to recreate an image of that era. What he gained from his research is a new perspective that enables him to grasp how this period fits into the flow of history as a whole. Lately, he has been vigorous in his efforts to convey the results of his research to society.

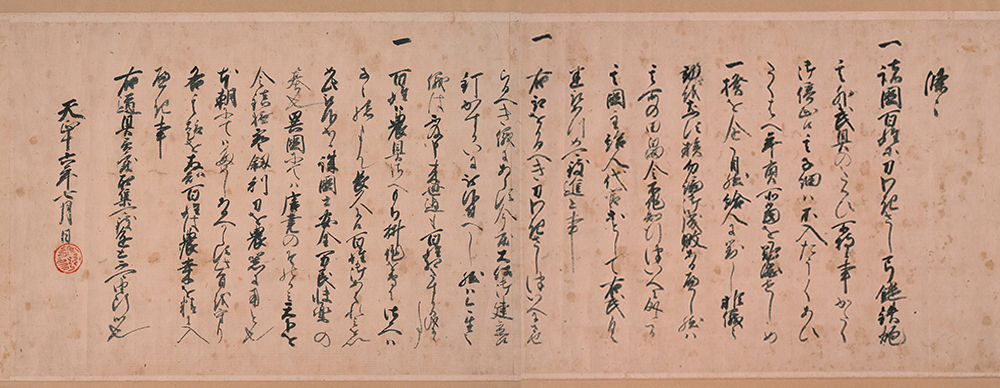

The study of history is more segmented than generally understood. As an example, my field of specialization is the early modern history of Japan, which is further divided into many specific areas. My focus is on political history from the Toyotomi administration to the early Edo period, and I conduct my research mainly by reading historical materials from that span of time. For instance, in conducting research on the Toyotomi administration, I read each of the enormous number of relevant historical documents one by one, such as the shuin-jo (shogunate licenses to trade) issued by Hideyoshi, and the letters written in those days between the daimyo (feudal lords), and then attempt to understand how they correlate with each other. In those days, information was exchanged by letters; thus, reading the letters progressively gives us insight into the ways of thinking and the personalities of Toyotomi and the other daimyo. Such understanding helps to recreate an image of the era.

We can learn a lot from a written document, and not just from the message it contains. For instance, the format, issuer, and intended recipient of a document are also significant information, and the fact that it has survived to the present day is another important point. Take, for example, a famous document called “Katanagari-rei” (Sword Hunt Decree), a shuin-jo issued by Hideyoshi in June 1588. It was found that only 11 original copies of the document remain, all of them without a recipient listed. Judging from the storage facilities which now own these documents, however, the recipients included the Shimazu clan, Tachibana clan, Kato clan, Kobayakawa clan, and the temples on Mt. Koya. Allowing that a certain number of these documents would be lost, the issuance is still thought to be limited. That is, even such a piece of key legislation as a sword hunt decree was not ordered to be sent to every daimyo. However, further study of the materials remaining in the hands of the daimyo clans revealed that the daimyo who did not receive the decree also followed it. Why? Because they proactively reflected the policy of Hideyoshi by collecting the information from Hideyoshi’s bugyo (magistrates) or other daimyo. Such consideration of these documents gradually enables us to grasp the essence of the power of the Toyotomi administration, which also forces us to revise the interpretation of other historical documents.

I have long been studying history in this style, which made me come to feel that the true recognition and interpretation of Japanese history depends on comprehending the entire history of Japan, not just of a specifically defined historical period. This may appear to be a natural, matter-of-fact idea to a non-academic person, yet the vast amount of accumulated historical material from each period requires a tremendous effort from a single researcher to read completely through. I believe, however, that rather than reading such material without a specific goal in mind, one should use their specialized area of study as the standard by which they critically examine research on other periods. Through doing so, the contours of their own historical views will gradually take shape. I have explained this concept in my book, Techniques for Grasping History (Rekishi wo Tsukamu Giho; published by Shinchosha), and I have recently published another book, an overview of the history of Japan titled Grasping the Flow of Japanese History (Nagare wo Tsukamu Nihon no Rekishi; published by KADOKAWA). I have also appeared on history programs on TV and radio, and supervised the entire set of volumes of Kadokawa Manga Study Series: Japanese History (Kadokawa Manga Gakushu Series—Nihon no Rekishi), to express this “essence of history” to as many people as possible. While these manga are intended for elementary school students, they contain knowledge at the same academic level as general university courses, so adults can learn many new things by reading them, too. This series has received support from a great number of readers, with two million copies being sold in a single year. I also enjoy taking part in an activity known as the “Kadokawa Exciting History Expedition,” in which I give history classes to elementary school students all over Japan by taking them to various historical places. I believe it is imperative that young students, as stewards of our future history, be equipped with a proper historical perspective.

Question: Is your research useful?

Answer: Politics, diplomacy, and business―none of these can afford to lack a historical point of view. We must make good use of history.

(We have asked twelve professors who contributed articles to this issue to answer the above question in 60 words or fewer. Professor Yamamoto's response appears here.)

Note: This article was originally printed in Tansei 33 (Japanese language only).

Answer: Politics, diplomacy, and business―none of these can afford to lack a historical point of view. We must make good use of history.

(We have asked twelve professors who contributed articles to this issue to answer the above question in 60 words or fewer. Professor Yamamoto's response appears here.)

Note: This article was originally printed in Tansei 33 (Japanese language only).