Music History Centered on Composers and Their Works, and the Reception History of Western Music in Modern Asia

Hermann Gottschewski

Professor

Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

An aficionado and performer of music himself, Professor Gottschewski specializes in musicology and comparative music theory. What is the kind of music history that does not focus on composers and their works? What is the “aesthetic present?” What is the relationship between western musical culture and Asia? And what was the role of a German musician involved in the composition of the Japanese national anthem, “Kimigayo”? The answers can be found in the following “music notes” played by Professor Gottschewski, who himself could be called a bridge between cultures.

Music history. Saying this phrase will likely conjure to mind composers such as Beethoven and their works. Naturally, however, there exist many other individuals and organizations throughout the history of music that have greatly influenced how composers have crafted their pieces. These agents include: instrument manufacturers, playwrights, arrangers, conductors, performers, singers, music publishers, recording engineers, critics, researchers, music teachers and students, fans, audiences, broadcasts, magazines, music stores, plays and movies using music, religious groups, political campaigns, and producers of commercials and background music, along with the laws and systems, organizations and institutions, and support and promotional efforts that have provided frameworks over the years through which music activities could progress.

The recording of music history as centered on composers and their works developed mainly in the 19th century. Such writings deeply reflect the social systems and values of that period, as well as the unique state of modern western art and music cultures (the so-called “classical music” of today) at the time. Accordingly, this kind of “music history” neither deals with every genre of music nor attempts to position classical music from a historical perspective. Rather, it could be said that this “music history” does nothing but explain the changes that occurred within the field of classical music. The veneration of composers as heroes and of their compositions as monuments succinctly conveys the attitude of Eurocentrism dominant throughout the 19th century. Even today, however, speaking of the histories of composers and their works is certainly not outdated. The modern relevance of such history is obvious from the large number of professionals engaged in the classical music vocation and how highly they are regarded socially, as well as the significant roles that the names of composers and their works still play in the classical music world.

Practically speaking, though, with regards to the written music history of the 21st century, we have to define the positions of the composers and their works not from the perspective of 19th century heroism, but from a contemporary standpoint. Unlike the many “historical facts” that are covered by the discipline of history in general, the works of classical music derive their historical significance not from the “facts” of the times and spaces in which they were created, but from how they are appreciated across time and space. For instance, one could say that through their works, composers who lived in the past can still communicate with audiences today. This capability is also known as a work’s “aesthetic present,” and it provides historical meaning to the work.

Practically speaking, though, with regards to the written music history of the 21st century, we have to define the positions of the composers and their works not from the perspective of 19th century heroism, but from a contemporary standpoint. Unlike the many “historical facts” that are covered by the discipline of history in general, the works of classical music derive their historical significance not from the “facts” of the times and spaces in which they were created, but from how they are appreciated across time and space. For instance, one could say that through their works, composers who lived in the past can still communicate with audiences today. This capability is also known as a work’s “aesthetic present,” and it provides historical meaning to the work.

Even a period that did not produce significant works can be regarded as an essential period in music history if it brought about new possibilities within the aesthetic present of existing works. A good example is the Meiji period (1868–1912) in Japan. In considering the Meiji era within the context of the history of western music, there is no need to bend over backwards to cite unsubstantial and inconsequential works as examples of music created during this period. Regardless of the lack of significant works produced during the era, the Meiji period played a major role in disseminating western music culture throughout Asia, and is therefore recognized as an important period in music history. The members of our laboratory utilize various methods to research why, by whom, and in what manner this dissemination occurred, as well as what subsequent influence it had on Asian music culture.

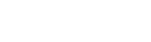

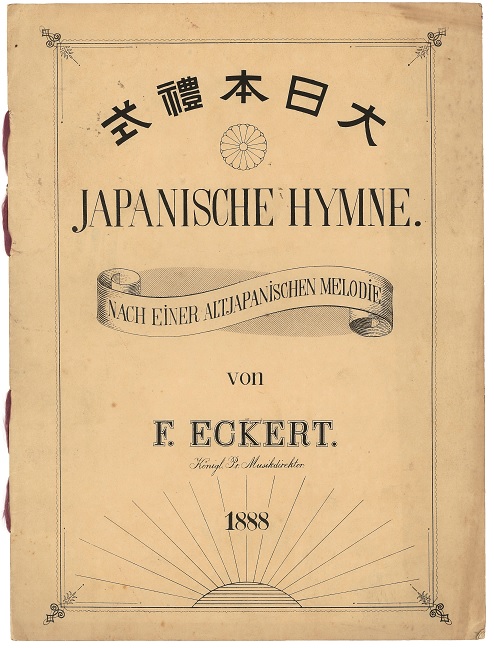

This year (2016), as a project for our laboratory, we commemorated the 100th anniversary of the death of Franz Eckert, a German who introduced western music to Asia, with a special exhibition in the Komaba Museum titled “Music Mastermind Eckert in Modern Asia―from Deep in the Prussian Mountains to Tokyo and Seoul.” The reason why Eckert’s name has endured in Japanese memory is because he participated in the composition of “Kimigayo,” the Japanese national anthem. Still, if we judge the role he played in music history as a whole, the positive impact he had as a “bridge between cultures” in influencing Japan’s reception of western music is much more meaningful than his role in “Kimigayo.” For more details on Eckert’s life and significance in music history, please visit the following link: http://museum.c.u-tokyo.ac.jp/images/eckert0528.pdf (Japanese language only)

This year (2016), as a project for our laboratory, we commemorated the 100th anniversary of the death of Franz Eckert, a German who introduced western music to Asia, with a special exhibition in the Komaba Museum titled “Music Mastermind Eckert in Modern Asia―from Deep in the Prussian Mountains to Tokyo and Seoul.” The reason why Eckert’s name has endured in Japanese memory is because he participated in the composition of “Kimigayo,” the Japanese national anthem. Still, if we judge the role he played in music history as a whole, the positive impact he had as a “bridge between cultures” in influencing Japan’s reception of western music is much more meaningful than his role in “Kimigayo.” For more details on Eckert’s life and significance in music history, please visit the following link: http://museum.c.u-tokyo.ac.jp/images/eckert0528.pdf (Japanese language only)

Question: Is your research useful?

Answer: Whether it is useful or not does not concern me too much. However, my eventual aim is to produce research that piques the interest of not just individuals in academia, but also that of the general public. If my research can make readers think, it may turn out to be useful in some capacity.

(We have asked twelve professors who contributed articles to this issue to answer the above question in 60 words or fewer. Professor Gottschewski's response appears here.)

Note: This article was originally printed in Tansei 33 (Japanese language only).

Answer: Whether it is useful or not does not concern me too much. However, my eventual aim is to produce research that piques the interest of not just individuals in academia, but also that of the general public. If my research can make readers think, it may turn out to be useful in some capacity.

(We have asked twelve professors who contributed articles to this issue to answer the above question in 60 words or fewer. Professor Gottschewski's response appears here.)

Note: This article was originally printed in Tansei 33 (Japanese language only).